Baker City Waterfront

by Chet Smith

A few years ago, Baker City designated an area on the northwest edge of town as

an official "industrial park," a term that was not common in the 1900"s.

However, Baker City had one of the first degree. It's what I refer to as the

"Waterfront." The name originated because it was the shipping and

transportation center for Baker City.

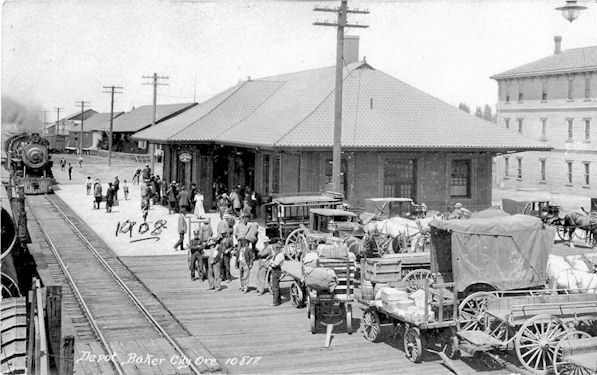

The Union Pacific Railroad Depot, the Sumpter Valley Railway Depot, the Railway

Express Company, and the Columbia and Crabil Hotels comprised the main hub of

the area. The U.P. Depot stood east of the main line of the U.P. tracks and

west of 11th Street, in the middle of what today is Broadway Street. In order

to continue west on Broadway, you had to detour about 100 feet north on 11th

Street, turn west around the north end of the depot, cross the railroad tracks,

turn back south a ways, then continue west on Broadway. After the depot was

razed in the 1960's, Broadway was straightened.

The depot was a red brick building about 100 feet long and 40 feet wide with a

red tile roof. One-hundred-foot-long strips of lawn extended from the north and

south ends of the building.

The front of the depot faced east on Broadway. Two large double door entrances

led to the waiting room. Once inside, ten double-sided benches provided seating

for customers. Entrances to the rest rooms on the south side were also inside

the waiting room. On the west side of the waiting room, jutting out onto the

platform, was the ticket and telegraph office. Quite often you had to wait

while the telegraph operator tapped out instructions in Morse Code to other

trains. The north end of the building housed the baggage room with doors to the

tracks and Broadway Street for dispersing and collecting baggage.

When the trains arrived, the baggage man would pull a wagon with four large

iron-rimmed wheels along the side of the baggage car, stack the baggage on the

wagon, and pull it into the baggage room where he sorted it for claim.

The U.P. Depot served six passenger trains a day. Three trains came from the

east and three from the west. Each train was loaded with passengers. Busses

from the Antlers Hotel and the Geiser Grand Hotel brought guests to the depot

to board the train, then waited to take arriving passengers to the hotels. In

addition, three or four cabs lined up at the curb in front of the depot for

people who needed a taxi.

Two of the six daily trains, one eastbound and one westbound, had a mail car

manned with U. S. Postal Service railway mail clerks who sorted the mail aboard

the train. Out-of-town mail clerks took their relief here in Baker, spent the

night, and then caught the next train back to their origination point. Most of

these men, probably ten at least, stayed in either the Crabil Hotel or Columbia

Hotel located just east of the U.P. Depot. Many of them spent their time in a

nearby cigar store playing rummy or pinochle. They very seldom went downtown.

At least ten mail clerks lived in and worked out of Baker. Most of them, I

think, worked the mail as far as Pocatello, spent the night there, then worked

the mail on the return trip to Baker.

You could post a letter in mail boxes located at either end of the depot at any

time. Or, if you happened to be there when the train was in, you could post a

letter in a slot in the mail car. The next morning, that letter would arrive in

Portland and be in the hands of the addressee by 10 A.M.

The 5 A.M. eastbound train carried newspapers from Portland. In the baggage car

were bundles of Oregonian, Oregon Journal, and Portland Telegram newspapers.

About twenty paperboys met that train every morning. They got their bundles of

newspapers off the baggage car, took them to the furnace room of the depot and

folded them for delivery.

Just west of the Union Pacific Depot and across the main line tracks was the

Sumpter Valley Railway (SVRy) Depot. SVRy was a narrow gauge train composed of

a steam engine, a combination baggage and mail car, and a passenger car. The

train came in from SVRy headquarters in South Baker every morning at eight and

loaded baggage and passengers headed to Sumpter, Bates, and, at one time, all

the way to Prairie City. The train returned at four in the afternoon bringing

people from the high country. Usually, 25 to 30 passengers got off at the SVRy

Depot every afternoon. Among the passengers were loggers and cattlemen from the

Sumpter Valley and McEwen area.

SVRy also operated logging trains up to half-a-mile long that brought logs from

the forests southwest of town for delivery to three sawmills (the Oregon Lumber

Company, White Pine Lumber Company and Stoddard Lumber Company) located along

the railroad tracks in Baker City. The White Pine and Stoddard Lumber Companies

had large log ponds that held the logs until they were later fed into the

sawmills and turned into lumber. The first step of the operation was to remove

the bark with a machine called the carriage. This machine also produced the

product commonly used for household fuel called slab wood. These three mills

employed well over 100 people.

Oregon Lumber Company also had a lumber mill in Bates, a company-owned town

with about thirty small houses where mill and store employees lived. In the

early 1960's after SVRy discontinued hauling freight, the company hired

truckers to haul lumber processed at the Bates mill over Dooley Mountain to be

transferred to U.P trains in Baker City. All of this ended when the Oregon

Lumber Company closed down operations in Bates and Baker City. All the houses

in Bates were sold and moved out -- most to Prairie City. Some were dismantled.

The Railway Express Company Depot was located south of the U.P. Depot with a

one-hundred-foot stretch of lawn separating the two buildings. The Railway

Express Company handled fragile materials like foods packed in ice and anything

you wanted delivered special and in a hurry.

Railway Express delivered merchandise around town with a horse-drawn wagon. At

four o'clock in the afternoon when work was done, the man who drove the horse

and wagon took the snap that attached a ground weight used to anchor the horse

during stops off of the bridle. After tying the reins up inside the wagon, the

driver turned the horse loose to follow its own lead up Broadway to Main Street

and across Main to the Red Front Barn, a livery stable, at Resort and Church

Streets. There, one of the stable hands took it in, unharnessed it, and put it

away for the night.

These horses were a special breed and a very noticeable attraction in town.

They knew the town just like the paperboys did. Eventually, small trucks and

vans replaced them. There's a picture of driver Art Chaves, who later became a

grocer, standing beside one of the trucks near the Columbia Hotel.

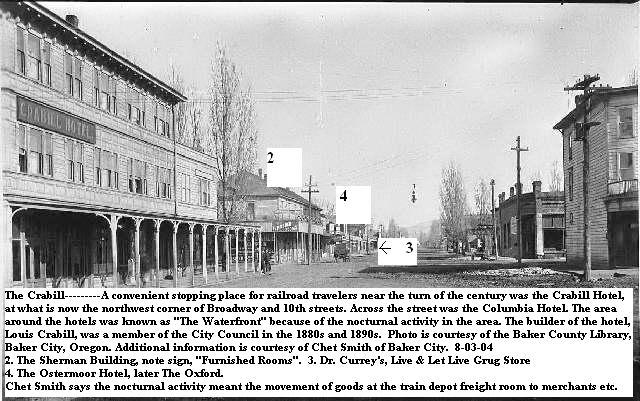

The three-story Columbia Hotel sat on a small piece of ground between 10th,

11th, Broadway and Jackson Streets, directly east of the Union Pacific Depot.

It had a cigar store, a restaurant, barbershop and rooms to rent. When it was

destroyed in the 1960's, it was hard to believe that that much hotel had sat on

such a small piece of ground.

On the southeast corner of 10th and Broadway (where the small engine repair

business is today) stood a stone building, which, among other things, was once

a butcher shop. It had a full basement with road-level iron doors in the

sidewalk leading to the basement. It is the only building of the era still

standing. From 1931 to 1933, it was my service station. For many years after

that, it housed car dealerships (including the original Chet Smith Motors).

Over the years, the building has been enlarged. The show room is the only

original part of the building.

East of the Union Pacific Depot facing Broadway between 11th and 10th Streets

(where the car wash is today) was the Crabill Hotel in a three-story wooden

building called the Crabill Building. On the ground floor of the building was

the Crabill Hotel lobby, with the entrance on the west end of the block, and a

large restaurant. In the lobby stockmen from the nearby stockyard sat at a long

table and studied the morning's newspapers to get acquainted with the day's

cattle market in the days before radio. Guest rooms were located on the upper

two floors.

Other businesses occupied the rest of the first floor of the building. One of

the most famous places was Bob Lowe's Café. Next, going east, was The Depot

Cigar Store, a cigar store and confectionary, which, by the way, belonged to my

dad. He sold candy, magazines, soda fountain drinks, and had three card tables.

The mail clerks spent a lot of time in there. Next, to the cigar store was a

one-man barber shop, Radabaugh's Barber Shop. He was almost always busy. Next

to the barber shop was the Depot Grocery, which was well stocked and enjoyed a

fine business.

On the other half of the block, north of the Crabill Hotel, stood a house and

an ice house that faced Church Street. The owner used to bring in cut ice from

the North Powder ice plant and pack it in sawdust. During the summer, he

delivered ice around town with horses and an ice wagon.

On the northeast corner of 10th and Broadway (current site of Ne-Hi

Enterprises) was the Sherman Hotel with rooms on the second floor. At street

level starting on the corner were Art Gard's butcher shop, Herb Sherman's soda

fountain, the OK Café Restaurant and a Chinese laundry. Two Japanese fellows

operated the OK Café. They opened every day at 5 A.M. Any paperboy could take a

paper in there and trade it for two hotcakes and a cup of coffee. It seemed

like it never got to the point where they didn't need any more papers. Every

kid was taken care of. Just across the alley facing Broadway was the Nugget

Saloon with its dirt floor covered in sawdust. This had previously been the

entrance to the livery stable.

This area was the center of the Waterfront, but many thriving businesses lined

the rail tracks north of the Union Pacific Depot to Campbell and south beyond

Auburn.

North of Broadway and west of the tracks was Baker Livestock Yards. This area

of about ten acres took in all of the ground between Broadway, Campbell, 12th

and 13th Streets with no cross streets in between. Today, it's the site of the

Ellingson Lumber Company office. Further north are some rental storage units.

In the early days, cattle drives came from Hereford, Unity, Sumpter, Richland,

Haines, Baker Valley and elsewhere ending up at the Baker stockyards with its

many pens and alley ways. About a dozen men worked at the stockyards feeding,

moving, sorting, and getting cattle ready to ship.

Cattle were loaded into cattle cars that lined the side track next to the

stockyards. When the cars were full, a switch engine picked them up and took

them down to the scales at Auburn and 9th Streets, where every car was weighed.

Then, the cars were brought back to the tracks and connected to a train. Some

cattle were shipped as far as Chicago.

North of Campbell and west of the tracks stood a tall flour mill called Baker

Mill & Grain Company. It bought grain from local farmers, processed it into

flour called Oregon Beauty Flour and shipped it around the state. They also

handled cattle feed, feed for milk cows and other grains. The building was

dismantled about four years ago.

East of the Union Pacific main line and north of Campbell were four little huts

where the railroad section crews kept their handcars. The handcars were a

platform on four small railroad wheels with a big T handle in the middle. The

men stood on each end of the handle and alternately pumped up and down

propelling the handcar down the track. No engine, just man power. Twelve to

eighteen men worked on tracks out of Baker. Each day they got their handcars

out of the huts and went one direction or the other to maintain the U. P.

tracks.

West of there, in the area of today's Baker Sanitary Service, was Bill Ellis

Transfer & Coal Company. He constructed a building where they could unload coal

from coal cars on a side track mechanically and store it. It sure saved a lot

of shoveling. He also had an office downtown at 1927 Court Street.

Moving south from Campbell toward the Union Pacific Depot, five businesses

relied on rail freight. The Union Pacific Freight Depot stood closest to

Campbell Street. It was the receiving and sending point for freight in and out

of Baker. When freight trains stopped at the depot, a switch engine uncoupled

cars meant for Baker and shunted them onto a side track for unloading at the

freight depot. In addition to the freight depot, a separate side track that ran

from Campbell Street along the east side of 12th Street to Church Street served

Ellis Transfer, Pacific Fruit and Produce Company, Allen & Lewis Company, Baker

Grocery Company and Marshall Grain Company (later Allison & Fortner Supply).

Union Pacific freight-handling employees unloaded boxcars at the freight depot

placing the freight into stalls, each marked with the name of a transfer

company operating in town. Then every morning transfer people came to the

depot, backed up to one of the freight depot's ten doors facing 12th Street,

loaded the freight they had received and delivered it to its intended

destination.

Likewise, freight that was brought into the freight depot in the afternoon to

be processed came back through those same doors and was loaded into the proper

outgoing boxcar. In those days, there were no trucks. All freight, going and

coming, was via train.

Just south of the freight depot was Pacific Fruit & Produce Company that had a

large warehouse with refrigerated units. It brought in watermelons by the

carloads and other perishable foods and fruits that were delivered to various

grocery stores around town. It employed about 20 people. Just south, was a big

warehouse occupied by Allen & Lewis Canned Foods Company. That warehouse is

still there. Between Allen & Lewis and the U.P. Depot was a large loading

platform that ran along the tracks.

The side track from Campbell to Church Streets also provided rail access to

Baker Grocery (across from Pacific Fruit & Produce and the freight depot) and

Marshall Grain Company (Allison &Fortner Supply).

The area south of the U.P. Depot and Railway Express Company also had many

businesses that depended on railway access. Stoddard Lumber Yard extended from

the Sumpter Valley Depot to near Auburn Street west of the rails. Occupying

about 20 acres and employing 75 to 80 men, it had a mill pond, a sawmill, a

planer, and the whole works. Later Tony Brandenthaler had a mill there,

followed by Ellingson Lumber Company. It was a great operation processing a lot

of timber and lumber. When it closed down due to a deteriorating lumber market

in 1996, Baker lost about 175 jobs.

Lou Lewis's Wood, Coal & Fuel Company was between Stoddard Lumber Yard and

Auburn Street. He got slab wood and board ends from the mills and delivered

them and coal to houses around town. It was a small operation, but Lewis made a

living at it. At the railroad crossing at Auburn between 7th and 9th Streets, a

crossing guard with a hand sign hung out in a little house about the size of a

one-holer. When needed, he stood at the railroad tracks directing traffic while

the switch engine moved freight cars back and forth. It seemed like he spent

more time standing with his sign out on the tracks than in his little shack.

Continuing south, still west of the main tracks, were the scales (where they

weighed the boxcars before adding them to outbound trains) and the Gyllenberg

Machine Shop. It was a general machine shop that did heavy-duty mechanical and

machine work, including the manufacture of wagons to sell to farmers. On the

southwest corner of Auburn and 9th Streets stood the McKim and Son Foundry &

Machine Shop (later the Timm & Son Foundry). This was one of the busiest places

in town. It did lathe and machine work and had a foundry that made patterns and

cast items of molten iron in its furnace for melting iron. SVRy locomotives

were repaired in a large side building. This building was torn down in 2009.

East of the railroad tracks, on the north side of Auburn, was Farmers'

Cooperative Creamery. The brick building and distinctive tall smoke stack are

still there. Every day its trucks traveled all over Baker County picking up

ten-gallon cans of cream from dairy farmers, as regular as the mailman. The

cans of cream were unloaded at the creamery where it was processed into butter,

cheese and other dairy products. Their butter was a favorite around town.

The Basche-Sage Hardware Company warehouse took up the entire area between the

creamery and Court Street. Seven or eight doors faced the side track for

unloading of mining and other types of machinery, hardware, and house wares.

About anything you wanted you could buy at the downtown Basche-Sage Hardware

store. It was known as the biggest store between Portland and Salt Lake City.

Two other businesses on 7th and Court Streets, Shockley Lumber (later Builder's

Supply) and Commercial Welding, depended on the railroad. Shockley Lumber built

fine lumber products in its large cabinet shop next to the tracks on Court

Street. It was a popular business employing about 25 people. Commercial Welding

employed about 75 men in the manufacturing of stock-handling equipment. It was

born in Baker, but expanded enough to move its main operation to Utah. We no

longer have the plant; we no longer have the people. However, the building is

in use today for the manufacture of playground equipment.

At one time, about 400 people worked in the Waterfront area along the railroad

tracks I just described. Today, only a handful still works there.

The intense activity of the old Waterfront no longer exists. Now, the railroad

depots and most of the businesses are gone. Nothing has ever replaced it and

probably never will. But, in its heyday, the Waterfront was a jump'n and jive'n

part of town.